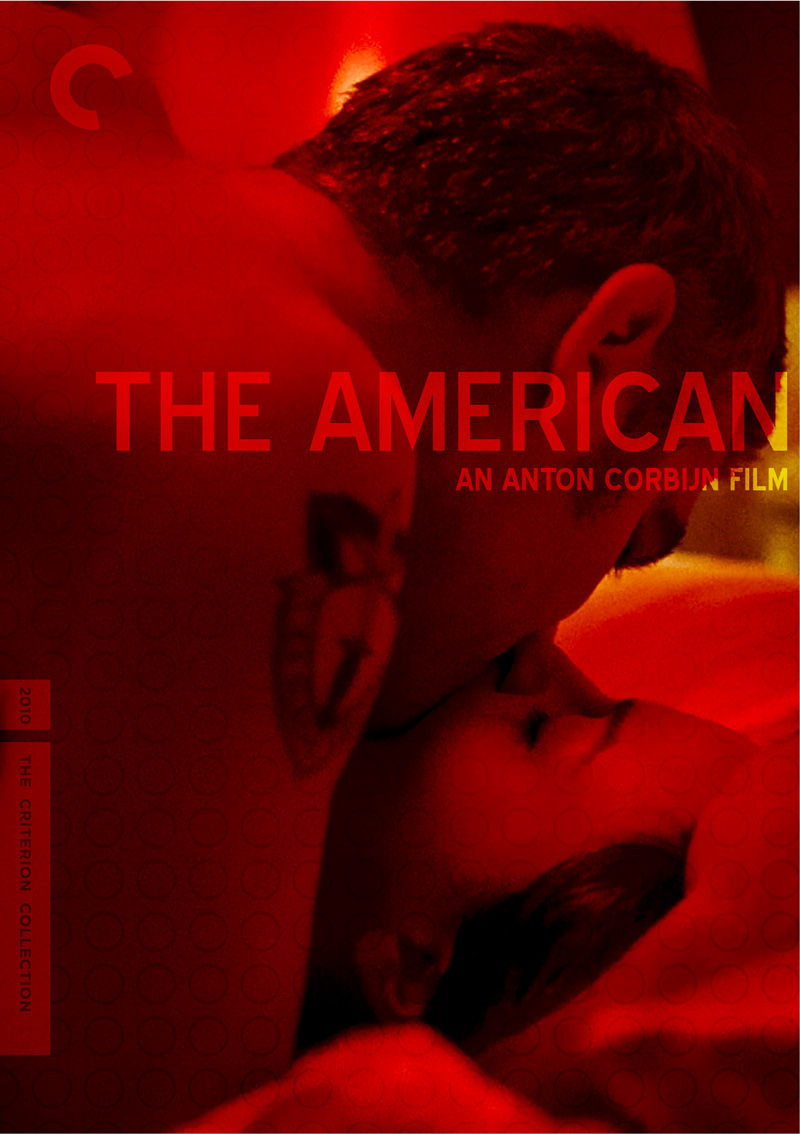

#8: The American by Anton Corbijn. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Anton Corbijn > An action-packed trailer for The American destroyed the film’s buzz on opening weekend. Filmgoers expecting George Clooney to be a James Bond-for-hire came out deeply disappointed when Corbijn chose to channel Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï and Fred Zinnemann’s The Day of the Jackal instead. On the surface, a slowly-paced thriller, but in actuality, the film works as a metaphor for many of us: We strive to excel at our craft of choice in order to find solace in our lives. Often, that comes in the form of a significant other, but sometimes circumstances force the two to be mutually exclusive. While it’s a seemingly obvious theme, it’s Corbijn’s photographic eye that compels us to remain transfixed on “Jack” and his intentions. A man of few words (which may shock those wanting Clooney’s usual gregarious on-screen presence), there’s a kind of obtuse seriousness that actually enhances the character’s mystique. Additionally, the salacious Violante Placido works perfectly as the forbidden fruit who sets the story into motion. Uneasy at times, The American is a rewarding adventure for the patient. And while it won’t necessarily teach any of us anything new, there’s enough emotional resonance to warrant a viewing.