2012 / Gao Qunshu > Beijing vs. Shanghai is always a fascinating study. It’s as if the higher ups in the government decided to draw a line between fun and no fun, between smiling and being a square, between the West and the East. And no matter how adventurous the barrage of insects on a stick outside Tiananmen Square is compared to The Bund, Beijing still comes off as the cold, bitter and smoggy brother of its brethren.

2012 / Gao Qunshu > Beijing vs. Shanghai is always a fascinating study. It’s as if the higher ups in the government decided to draw a line between fun and no fun, between smiling and being a square, between the West and the East. And no matter how adventurous the barrage of insects on a stick outside Tiananmen Square is compared to The Bund, Beijing still comes off as the cold, bitter and smoggy brother of its brethren.

Maybe that’s why Beijing Blues is so incising: the city that holds itself like a cold, locked down safe is cut in half. It shows its weaknesses through the eyes of a police captain like anyone and everyone. Sure, he has a certain conviction to do good, but that doesn’t keep him from telling his wife to stay in the kitchen. That’s not surprising, though: People excel in some areas and are weak in others, balancing out their humanness. And Beijing is, regardless of the attempts by its government superiors, a city of such humans.

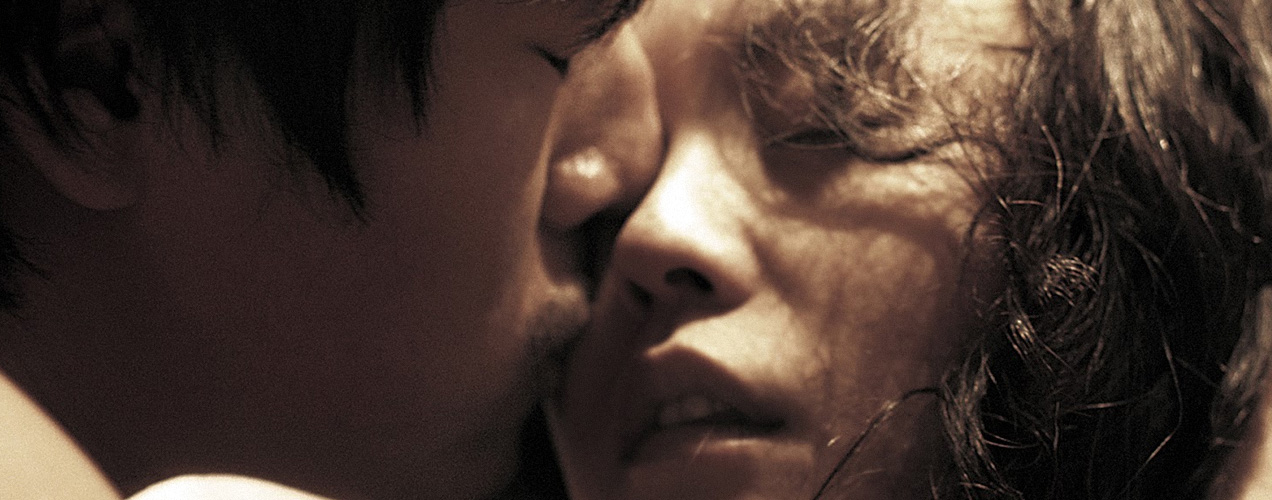

Beijing Blues is a character study, both of the police captain Zhang as well as the city in question. In their humanity, there are details of self-preservation instilled: certain thieves, for example, only chase after non-Beijingers. And justice, it is said, should not come at the expense of breaking the law. The film undfolds as a police procedural though without the glamour of Johnnie To’s crime epics. Mood-wise, it’s hard to pinpoint it as a comedy or drama as some scenes are just plain ridiculous. Then again, a city as big as Beijing surely has such moments. With its near-sterile, calculative approach to storytelling, one could argue that this is a Jia Zhangke film with cops and robbers. It could even be dubbed an “action contemplative” film filled with long shots of the capital’s streets against the backdrop of local pop music, including a particularly gorgeous scene where Zhang is followed through the night by a man of mystery. Why is he chasing Zhang? He’s not violent, but he’s obsessive. It’s one of the film’s small mysteries that gets answered at just the right time.

Unique to the film is the cast list: When the credits roll, not only do we find out the names of the actors, but also their real-life professions. Our police captain is played by Zhang Lixian, a “well-known publisher.” Others include “a security guard in Shuangyushu Police Station in Beijing,” a “well-known TV presenter” and a “director and playwright of experimental modern drama.” In short, a cast of non-professionals filling out the roles of characters in the city they inhabit. Is this simply a love letter to Beijing? Maybe, but one thing’s for sure: Its victory at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards for Best Picture was both shocking and impressive. Though one would hope Beijing Blues was rewarded for its filmmaking, there’s undoubtedly a foundation of respect for getting the mainland capital to tear down its facade, showing its people to be like you and me, getting its humanity out in the open.