2007 / Len Wiseman > Die Hard films are about being in a position of impossibility. The building, the airplane—they made sense. But when Die Hard: With a Vengeance successfully moved away from that formula, the title became a bit of a misnomer. With Live Free or Die Hard, Wiseman moves even further away from the original premise, and those who remain loyal to the originals will undoubtedly be disappointed. But I’ve moved on, and this is one hell of an action-packed flick. Arguably the best summer adrenaline rush since Mission: Impossible 3, once McLane starts, he never stops (although Maggie Q almost makes that happen). Enjoy the mindlessness, don’t think too hard about the economics or the technology and let Willis help you forget that he’s 52 years old.

The Lives of Others

2006 / Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck > Every year, there are a few films that have nearly flawless executions. In 2006, The Lives of Others just might have led that pack. While I couldn’t find myself as emotionally attached to the story as those who are natives of Germany or have been in similar collectivist situations, interest in the film rarely waned once the plot started to roll. The story of the East German Stasi is not one I was previously familiar with, but the 1984-esque paranoia that rung around the film was thick, congestive and effective. Personally, I couldn’t agree with some of the character development and emotional manipulation that occurs as the show goes on, but overall, I also can’t be angry that this beat out Pan’s Labyrinth at the Oscars for Best Foreign Film. There’s much merit in its cold, calculated success.

Paprika

2006 / Satoshi Kon > Maybe the shine of pseudo-existential anime is new to America, but this has been done before (notably in Ghost in the Shell and Akira, but most recently in Satoshi’s own Paranoia Agent). For all its beauty, I can’t help but think that Paprika falls short in actually showing us something new. And because of that, I also can’t really justify the complexity of the storyline and obtuseness of the conclusion. In Satoshi’s oeuvre, Tokyo Godfathers still reigns supreme in my book.

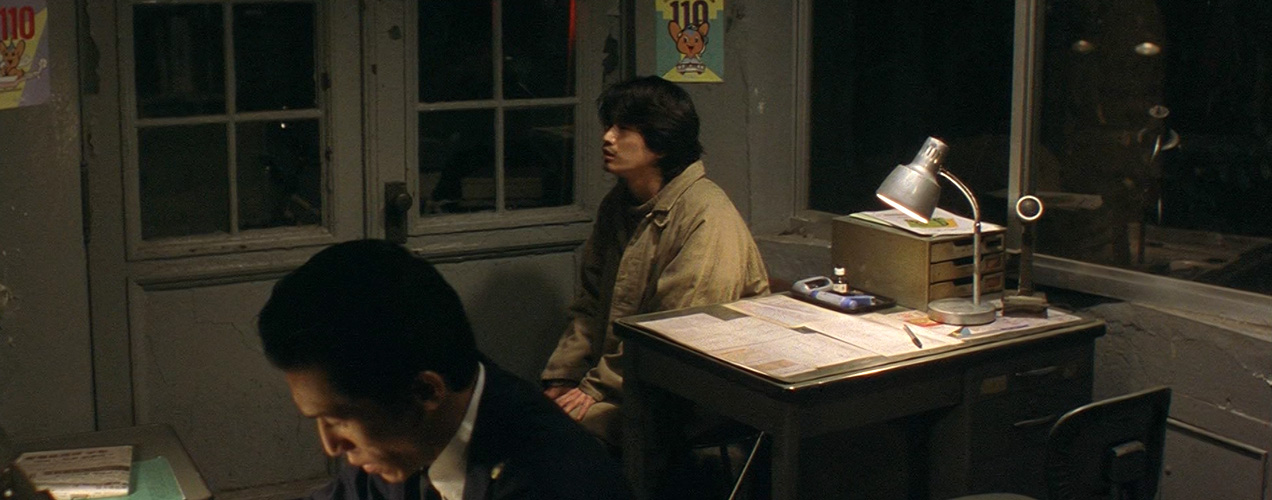

Cure

1997 / Kiyoshi Kurosawa > Visible horror is often forgettable. It’s the creepy feeling that remains after the film is over that really drives home the chills. Unfortunately, most films fail at this and end up being filled with unnecessitated gore or overtly pretentious psychological mazes. Cure, however, connects with the inner-horror of every man and woman, filling us with a sense of paranoia that may very well stay with us at days on end. What’s amazing, though, is that that feeling isn’t necessarily “evil,” as most horror would expect us to presume. It’s simply a feeling that seems almost eye-opening and surprisingly natural.

Knocked Up

2007 / Judd Apatow > It often seems that for a film about relationships to be good, there has to be some destructive forces involved with cynicism abound. But Apatow is better than that: Judging from his work on Freaks and Geeks, where he tackled a topic of much maligned stereotypes with a level of reverence unfound elsewhere, he’s figured out how to turn common, beaten topics into constructive expositions. In Knocked Up, he successfully balances the jokes, the pop culture references (often needed to understand the nuances of the male protagonist) and the reality of an accidental pregnancy. It’s touching, it’s commendable and it’s got Matsui.

Four Eyed Monsters

2006 / Susan Buice & Arin Crumley > I don’t deny that the intent here is of great interest: How has the world of relationships evolved with the advent of social networking for those who are still somewhat lost, especially in their twenties? And with that, it starts off quite strong. But somewhere along the way, it digresses into issues of identity that are specific to a certain demographic (of which I can’t entirely relate to). Ultimately, it’s a deeply personal film by Buice and Crumley, who also star, and one that should attract those who have a certain sense of disillusionment from urban living vs. original expectations.

Memories of Matsuko

2006 / Tetsuya Nakashima > Considering I couldn’t bear more than 30 minutes of Nakashima’s Kamikaze Girls, imagine my surprise when I found Memories of Matsuko creeping up my mind months after having watched it. While it may be a ridiculous musical with an abrasive color palette, misplaced violence and oodles of sexual innuendo, it also ends up falling just short of being a masterpiece of human resilience.

2006 / Tetsuya Nakashima > Considering I couldn’t bear more than 30 minutes of Nakashima’s Kamikaze Girls, imagine my surprise when I found Memories of Matsuko creeping up my mind months after having watched it. While it may be a ridiculous musical with an abrasive color palette, misplaced violence and oodles of sexual innuendo, it also ends up falling just short of being a masterpiece of human resilience.

Miki Nakatani’s portrayal of Matsuko is one of the year’s great performances, showing a wide emotional range while still successfully hitting every note. Her ability to be a chameleon is further complimented by Nakashima’s storyline of life’s ironies and heartbreaks that span multiple occupations and decades, creating an epic of personal proportions. This is a story about one person, a very normal person who has dreams like the rest of us. And this is the story of one whose dreams don’t come true in the fashion that was intended, but magically we find solace in the fact that life isn’t dictated by those failed dreams.

Happy Together

1997 / Wong Kar-Wai > Undeniably my least favorite Wong Kar-Wai film, but not because of the obvious subject matter: The problem was that it felt too easy. When you have a character like Ho Po-wing—that bastard significant other who’s selfish but somehow always comes back to haunt you—it becomes an easy to use conflict creator that tires quickly. It lacks the imagination of Chungking Express and the subtlety of In the Mood for Love, but saves itself by retaining the visuals and music that are so pertinent to Wong’s oeuvre.

The Hole

1999 / Tsai Ming-Liang > While I’ve gotten somewhat used to Hou Hsiao-Hsien, it’s still been a bit of a dogfight “getting” Tsai’s films. The question I find myself asking is: If nothing really happens in a film, do you go out of your way to find meaning? I think no, mostly because if we did that with every film, it’s possible to find loads of layers that were not intended to begin with. And in many ways, I still find intention to be one of the cornerstones of filmmaking. (It is, of course, possible to not execute your intention properly but still result in a better film than originally intended—and judging that is quite another dilemma.) Anyhow, The Hole and its semi-apocalyptic romantic musical isn’t for everyone. Tsai remains a director you love or you hate, and while I won’t go to the polar negative, I can’t say I’ve warmed up to him by any means.

A Hole in My Heart

2004 / Lukas Moodysson > Moodysson knows how make one feel miserable while watching a film. In Lilya 4-Ever, he did it in a way where the audience could find this misery justifiable to a point, but here, it’s an absolute joke. Any issues of morality or relationships that are supposedly being explored is a cover for what is essentially a shock-piece, filled with unnerving moments that result in no enjoyment and leaves the audience feeling sick and even guilty for viewing this in the first place.