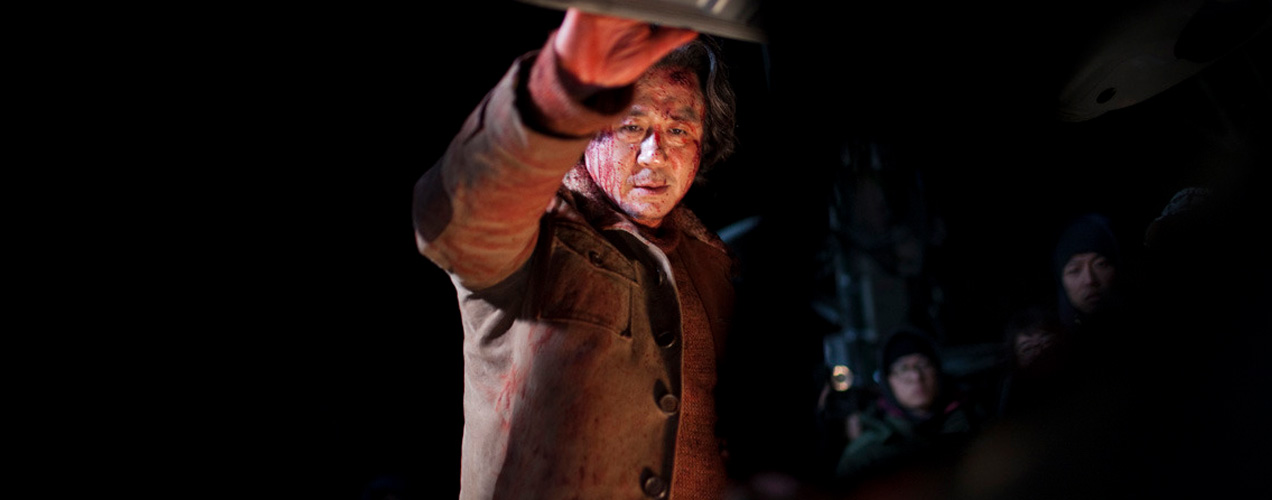

2011 / Nicolas Winding Refn > The worst thing about Drive is the hideous, misuse of Mistral during the credits. You sit there, as Ryan Gosling drives into the night, wondering if you’ve been transported to a grittier version of Miami Vice. Maybe genre films remain an insular interest because the kitsch factor is too embedded in their culture? After all, this is the font that graced the intro of television’s Night Court.

But then the film unfolds. And sets up. And takes off. And during this ride, which can effectively be described as a classic noir tale with a penchant for real violence, there is nary a hole that can be poked. Every second is necessary, every shot elegant, every piece of music supports the action on the screen. Every question normally asked of a film, this one answers either with some level of extrapolation or faith in its characters. Gosling, credited simply as “Driver,” is reminiscent of Clint Eastwood’s The Man with No Name. We gradually discover over time that he’s exactly the kind of person missing in 99% of Hollywood cinema: One that doesn’t cop out. That, in itself, is a tremendous victory.

As those who’ve watched his Pusher trilogy as well Tom Hardy’s brilliant, psychotic coming-out party in Bronson can testify, Winding Refn is a momentous talent. In fact, the lyrics of Kavinsky and Lovefoxxx’s “Nightcall,” which overtures the opening sequence, speaks of both the director as well as Gosling’s Driver: There’s something about you, it’s hard to explain. They’re talking about you, boy, like you’re still the same. In short: They are not to be underestimated. Drive shows the maturation of Winding Refn as a controlled director, Gosling as an action star and together they’ve come up with a fine piece of entertainment that’s a beauty to look at, satisfying to watch and evocative enough to remember.