1982 / John Carpenter > It doesn’t matter how much the special effects in The Thing have aged, what stood out for me is the sheer ingenuity of its intentions. The creature from outer space is keenly unique, grotesque and memorable, but more importantly, the writing is taut, imaginative and the pacing fills every scene with tension. Color me absolutely surprised that I enjoyed this that much, as I was pretty much expecting some sort of kitsch fare that was good for a laugh more than a scare.

Synecdoche, New York

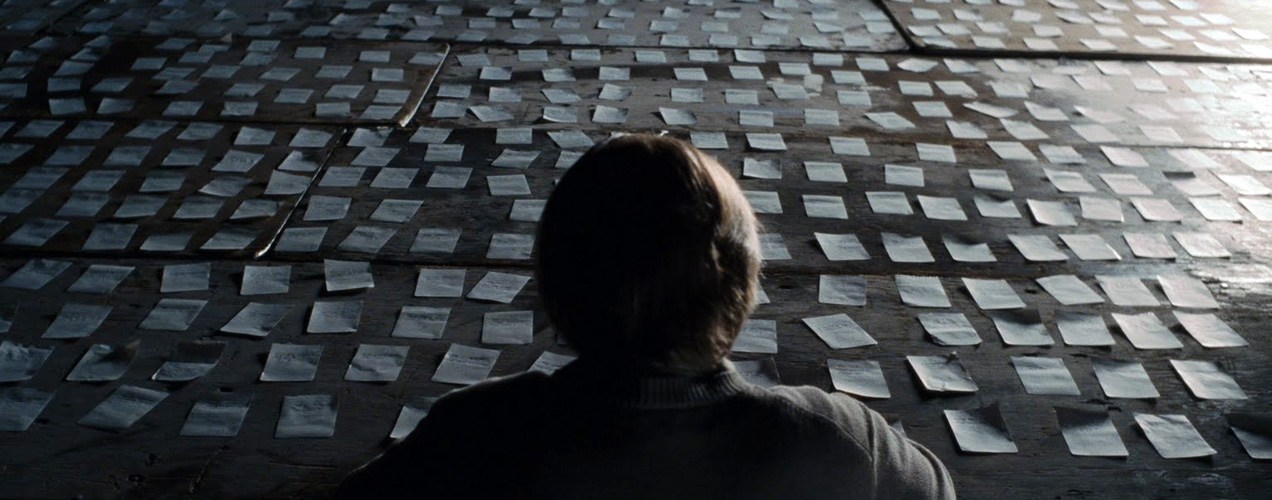

2008 / Charlie Kaufman > Here’s a thought: Twenty years from now when we look at 2008’s global filmography, Synecdoche, New York will be the year’s towering achievement. Kaufman’s directorial debut is an injection of a life into the bloodstream, and the way it shakes down our internal struggles and chaotic delusions is truly magnificent. It’s imperfect in ways it should be, in that pseudo-bullshit philosophical manner that nobody can really explain. And because it tries to explain things so minimally, it becomes the viewer’s movie. Everyone can live this, everyone is this, and as crazy as it sounds, sometimes I find myself thinking that it’s about me. The aging of man is a topic that has been touched upon with much success in the past (Ikiru, Wild Strawberries) but never like this. It’s something only Kaufman can do, and it will undoubtedly polarize, fascinate and confuse for years to come.

Horsemen

2009 / Jonas Åkerlund > You know how a well-written thriller is supposed to be one step ahead of the viewer, making sure that the tense atmosphere continues until the very end? This isn’t one of those. Too often, the genre conventions fell into place and I found myself one step ahead of Dennis Quaid’s detective in charge of discovering the Horsemen behind some grizzly murders. In and of itself, this could survive if the story is good, but even that fails because of lack of scope. It’s as if someone promised me a trip to Paris and then took me to Philadelphia—it simply doesn’t work. No matter how well intentioned the ending may be, disappointment remains. All this is quite sad in two respects: Akerlund was on my list of directors to watch after a risky yet satisfying effort in Spun. Also, it was nice to see Zhang Ziyi play something different (in this case, a creepy, slithering snake of a woman with devious intentions).

The Ox-Bow Incident

1943 / William A. Wellman > The Ox-Bow Incident is a simple story of conscience done very, very well. Often reminding me of Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, the film’s crux is a lynch mob hellbent on punishing some rogue cattle rustlers for the crime of murder. How this unfolds isn’t particularly novel, but is undoubtedly daring for a film made in 1943. Henry Fonda is instantly watchable, as is Dana Andrews and Anthony Quinn as a couple of men that get held up at the stake. If only the resolution didn’t delve into a sort of preaching mode, this would have stood out as a better testament of mob mentality.

Gomorra

2008 / Matteo Garrone > Gomorra is a deeply rich film that lacks the sensationalist touches we often see in mafia dramas. Remember how Heat was a poetic version of cops & robbers? Well, this is what you get when you strip out the loud violence and criminal glamour. The multiple storylines seem a bit daunting initially, but they end up really impressing on the basis of their meticulousness. Based on the book by Roberto Saviano, Garrone’s adaptation really works to stress the capitalist reaches of the modern Camorra, the Naples-based organization on which the works are founded upon. From the typical youngster wannabes to the world of waste disposal, the film is a nuanced treat into the daily ongoings. It’s so real that Saviano himself has been forced into exile due to fear of death. This is impressive stuff for the patient viewer, and almost honorable because it doesn’t build up the lifestyle, but rather puts it in perspective from both local and global viewpoints.

The Night of the Hunter

1955 / Charles Laughton > After Robert Mitchum’s turn as the dashing anti-hero in Out of the Past, I found it refreshing to see his portrayal of a so-called holy man with a batshit crazy mind. The man gives you the creeps in The Night of the Hunter, with his wild religious rhetoric and instantly suspicious demeanor. What tricks me is that I can’t figure out what Laughton was up to. The film’s hard to figure out because it’s not simply a good vs. bad story, as it has shades of a fable and a darkly Biblical undertone. But all that withstanding, everything simply falls apart at the end. Symbolically and fundamentally, it becomes a jumbled mess. Sure, it’s possible to justify everything that happens, but it just doesn’t feel acceptable to a rational mind. Either way, one thing is for sure: This has some of the finest cinematography I’ve ever seen in a black & white film. Stanley Cortez uses beautiful, stark angles and really captures the depth of what one can do without color.

Frankenstein

1931 / James Whale > Regardless of what kind of classic status Whale’s Frankenstein may hold in the annals of cinema, the fact that it mostly circumvents the humanist touches of Mary Shelley’s original work keeps it from actually being a great film. So much of this hinges on the simple fact that the creature is never given a chance to grow and mature. In the novel, it’s Frankenstein’s fear that drives the creature into madness, but here it’s the doctor’s assistant making a mistake by providing an “abnormal brain” for the experiment. Therefore any sort of commentary the film tries to make becomes null. Criminal brains do criminal things, so where’s the lesson of morality and the God factor? Shelley tried to warn of taking life and death into the scientific framework whereas Whale gives us no particular basis to believe that it’s good or bad, simply that you have to make sure to pick the brain of a gentle, loving person in order to create a creature that may also be gentle and loving. When the viewer already expects the worst, then the compassion for the creature is lost, and in the process, so is the wonder and warning within the story.

Chaplin

1992 / Richard Attenborough > Considering the spotlight on Robert Downey, Jr. post-Iron Man, it’s shocking that more people haven’t brought up his magnificent performance in Chaplin. Even now, watching Charlie’s flicks, I can’t help but substitute in Downey’s face without a worry. At age 27, he mimicked the lives of one of the most magnetic performers in cinematic history yet it feels as if no one remembers. Some of this blame arguably goes to Attenborough for taking an unorthodox approach to a biopic by focusing on Chaplin’s love affairs to progress the storyline, which led to slightly uneven pacing and treatment of his work as almost secondary. While this may have resulted in mixed critical response, there’s no denying that his life did indeed revolve around women, and that the longing for his first love led to multiple marriages to younger and younger women. Furthermore, there was at least 12 minutes cut from the director’s version and almost two hours left on the cutting floor altogether. Who knows how much better this would have made it, but even as it stands, it’s an incredibly enjoyable piece about a fascinating icon of culture and is worth viewing to get a glimpse into him and his works as well as the ridiculousness of the McCarthy era.

The Girlfriend Experience

2009 / Steven Soderbergh > The big question everyone will be asking is, “Can Sasha Grey act?” Sad to say, the pornographic star’s crossover role has such a limited emotional palette that it’s hard to tell. Her character is the subdued type, quiet and reserved except for bursts of emotion inflicted at a loved one. And the story itself is Pretty Woman with a tinge of cynicism. Credit to Soderbergh for giving the girl a chance (as I’d love to see her do more work outside of the realm of the skin and saliva), and for fleshing up the sights of Lower Manhattan true to life. But from those basics, the film is a study of the world’s oldest profession in its modern setting without really bringing anything we didn’t already know. Were it a character piece, I could understand, but even that doesn’t seem to really fit into the details of the script. Even the stints at social commentary via the clientele’s morning shoptalk is too lackadaisical to derive some level of interest.

State of Play

2009 / Kevin Macdonald > Frankly, there was no way this film could make me happy. The original 2003 BBC miniseries on which this is based is one of my single favorite pieces of television ever. It’s clever, thrilling and intelligent. John Simm in the lead is downright brilliant and the rest of the cast is near perfect. But in the process of cramming six fantastic hours into two for the global mainstream audience, quite a bit of detail and charm has been lost. While it remains a rather well-made film, the last third seems rushed and increasingly trite. The pacing of the movie kills the appreciation of the character motivations and starts insulting the viewer’s intelligence. Incidentally, the same storyline in the miniseries successfully orchestrates these emotions. Thus, I can’t stress enough that everyone should give the original a chance. Avoid a couple of clunkers this summer and spent those extra four hours diving into this riveting Brit drama and come out much more satisfied.